This series of five paintings marks my first attempt to stabilize fragile materials such as coal dust, ash, and rust on 30×40 cm canvas. Each work draws directly from classical Chinese poetry—Du Fu’s vision of Mount Tai, Li Bai’s waterfall, Zhang Ruoxu’s moonlit river, Wang Zhihuan’s setting sun, and Lin Bu’s pavilion amid shadows. The poems, as old as the coal itself, become renewed through a material language that is both elemental and volatile.

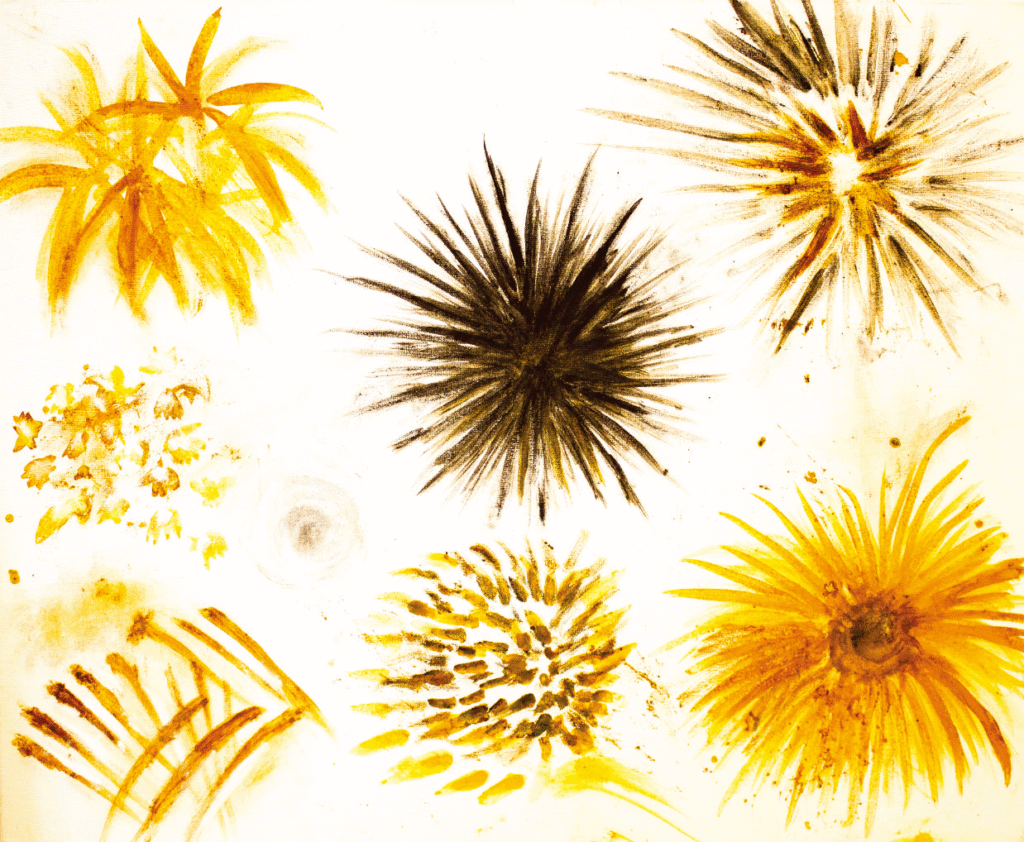

The process demanded painstaking experimentation: testing how coal adheres to oil primer, how rust pigments shift with humidity, how ash can remain visible without vanishing. What emerges are not merely images but fragile monuments, where the instability of matter echoes the impermanence sung by the poets.

This fragility opens new questions for me. How can such works be preserved without erasing their material truth? During this residency, I want to explore preservation on multiple levels: • Technical — experimenting with fixatives, transparent resins, or traditional binding agents to stabilize the surface. • Digital — photographing, scanning, and even projecting the works, so that their disintegration becomes part of their afterlife. • Conceptual — treating fragility not only as a problem but as a poetics, where the very impossibility of permanence is a reflection on memory, history, and survival.

In connecting ancient Chinese verse with coal and ash, I situate my practice between personal memory and collective inheritance. At Delfina Foundation, I hope to deepen this inquiry: to test methods of working with unstable matter, and to situate my practice in dialogue with London’s own layered histories of industry, literature, and material decay.

This coal is from Fengcheng, Jiangxi — a city whose identity was forged by coal mining since the Tang dynasty. For centuries, coal was the economic lifeblood here, shaping livelihoods and rhythms of life. In my childhood, every household relied on coal: its crackle was the sound of winter nights, its soot a constant on our walls and hands. Coal represents a way of life that is vanishing — replaced by gas, electricity, and global calls for decarbonization. In the contemporary imagination, it now carries a double meaning: once the proud foundation of progress and prosperity, it is also framed as a symbol of pollution and obsolescence. This tension mirrors Britain’s own trajectory: coal powered the Industrial Revolution, lit up cities, drove locomotives, and forged steel empires. The “Black Country” became a global emblem of industry and modernity — but also of smoke-choked skies. Today, Britain has closed its last coal mine (2015) and last coal power station (2024), turning a page on this epoch. In my practice, I choose to reclaim coal as a cultural and poetic material rather than leave it as an artifact of decline. It becomes pigment and ink in my Poetry Painting series, where I render classical verses and Tang Xianzu’s imagery in coal dust. This act reanimates coal’s semantic field: it is no longer just fuel, nor merely a pollutant, but a bridge between ancient literati aesthetics and contemporary critical reflection. In this way, coal is simultaneously memorial and rebellion — remembering a past way of life while refusing to let it be relegated to silence. It allows me to stage a dialogue between my rural roots and a global art discourse, insisting that even a material as politically loaded as coal can still carry subtlety, fragility, and poetry.

This red earth is both material and metaphor. It comes from the soil of my childhood landscape in Jiangxi and is ground into pigment for my paintings and drawings. Working with it means literally bringing the ground into the work — the iron-rich hue recalls blood, rust, and sedimented time. Together with coal and ferric sulfate, it forms a palette of the earth’s memory, carrying the weight of labor, ancestry, and cycles of erosion and renewal. By using red earth directly, I collapse the distance between studio and field, artwork and terrain, body and ground.

Ferric sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) plays a central role in my ongoing material research. Beyond its chemical identity, I treat it as both pigment and agent of transformation: when applied to canvas or xuan paper, it reacts with moisture, air, and other materials (coal, ochre) to produce unpredictable hues ranging from deep rust to golden ochre.

This bottle of ferric sulfate has been with me through multiple experiments — it is part of my “studio ecology.” By including this image in my documentation, I foreground the process and materiality of my work, emphasizing that the artwork is not only the final painting but the entire chain of reactions, trials, and failures that precede it.