Spring River Enters the Old Year 江春入旧年

This work draws from Zhang Ruoxu’s Spring River in the Flower Moonlit Night, particularly the line “The spring river enters the old year.” Using coal dust and rust, the image blurs the boundary between past and present, letting the moonlit river become a metaphor for time’s endless flow and the recurrence of longing.

Waterfall of Three Thousand Feet 飞流直下三千尺

Inspired by Li Bai’s Viewing the Waterfall at Mount Lu, this work uses gravity and diluted coal pigment to create a vertical rush of black, as though time itself is plunging downward. The piece invites viewers to experience the weight and grandeur of natural force in motion.

Summit Over All 会当凌绝顶

This work draws from Du Fu’s Gazing at Mount Tai, especially the line “When I reach the summit, all mountains seem small.” The mountain, rendered in coal dust, stands upright like a spiritual monument, while the rust-colored sky swirls with energy, turning the scene into a vision of striving and transcendence.

Subtle Shadows and Faint Fragrance

Inspired by Lin Bu’s line “Sparse shadows slant across the clear shallows; faint fragrance drifts under the moon at dusk,” this work depicts a glowing pavilion hidden among tree branches. Coal dust and rust react to form a delicate network of silhouettes, turning the scene into a suspended moment of quiet illumination.

Long River, Setting Sun 长河落日圆

This work reimagines Wang Zhihuan’s iconic verse “Long River, Setting Sun Round.” The meandering white line becomes both river and traveler’s road, evoking themes of distance, persistence, and the inexorable passage of time beneath the setting sun.

To KnotTo Knot IsTo Knot Is to Hope — and Still I Push the Stone

EN:

This work gathers a tree of branches, a knotted rope-net, a stone with my handprints, and drifting smoke — four elements that map my meditation on time, memory, and living. The tree recalls the deep-time process of plants turning into coal, suggesting that all life is sedimented time. The knotted net references ancient record-keeping — quipu, knotting — but it sags like Dalí’s melting clocks, signaling that even our systems of memory eventually slacken and fail. The stone is my Sisyphus: I have pushed it repeatedly, leaving white handprints as small medals of effort. This gesture is not merely symbolic; it is physical labor, grounding me in the present. The smoke drifts upward and slips through the net — a reminder that the most beautiful and poetic moments cannot be archived, captured, or posted. In a time when life is often lived to be recorded — staged for the feed, edited into proof — this work asks the opposite: What if we simply live? What if the real task is to push the stone, to feel its weight, to breathe with the smoke, knowing it will vanish? This installation concludes not with despair but with a stance: even though the net fails, I choose to keep knotting, keep pushing, keep living. This is my existential response: life is not a spectacle to be preserved but a task to be lived, every second an act of resistance against nihilism. ⸻ 中文:

这件作品汇集了树枝搭建的树、结绳的网、带有我手印的石头和缓缓升起的烟雾——四个元素共同构成我对时间、记忆与生活的思考。树呼应植物成煤的深时过程,暗示一切生命都是时间的沉积。绳结网呼应古老的记录方式——结绳记事——却像达利画中软化下坠的时钟,象征即便是记忆的系统也终会松弛、失效。 石头是我的西西弗斯之石:我一次次推它,在上面留下白色手印,像一枚枚努力的勋章。这不是象征性的动作,而是真实的体力劳动,让我落地、让我回到当下。烟雾缓缓升起,却总从网中溢走——提醒我最诗意、最美的瞬间是无法被归档、捕捉或发布的。 在一个生活常常被用来“记录”的时代——为社交媒体而摆拍、剪辑、证明——这件作品反问:如果我们只去好好生活呢?如果真正的任务是推石头、感受重量、与烟雾一起呼吸,明知它会消散呢? 作品的结论不是绝望,而是一种立场:即便网兜不住,我依然选择继续打结、继续推石、继续生活。这是我的存在主义回应:生活不是为了保存,而是为了去活,每一秒都在对虚无主义进行抵抗。

Waiting Under the Knotting Tree – Performance Still 结绳树下的等待 —— 行为表演静帧

EN:

This photograph is part of a durational performance staged inside the installation Knotting Tree. By sitting quietly beneath the rope-net “canopy,” I consciously reference Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, where waiting becomes the very content of existence.

Here, the stone bears the traces of my earlier labor (pushing the rock, leaving handprints), and yet the act of sitting suspends all action — it is a paradox of life: we labor and mark the world, yet we are also asked to wait, to pause, to endure the passing of time.

For me, this work explores existentialism not as despair but as attention — to sit and feel time stretching, to notice the dust in the air, the subtle movement of smoke, the sound of my own breathing. It is a refusal to let life be reduced to productivity or spectacle; the waiting itself becomes a form of resistance, a quiet insistence that being present is already meaningful. CN:

这张照片是我在装置《结绳树》内进行的持续性表演的一部分。我坐在绳结网状“树冠”下,直接呼应塞缪尔·贝克特的戏剧《等待戈多》,让“等待”成为存在本身的内容。

这里的石头保留了我先前劳动的痕迹(推动过的石头、手印),而坐下的动作则暂停了所有行动——这是一种生命的悖论:我们劳作、在世界上留下痕迹,却也被迫等待、暂停、忍受时间的流逝。

对我来说,这件作品探索存在主义并非作为绝望,而是作为感知:坐着感受时间被拉长,注意空气里的尘埃、烟雾的微微游动、自己的呼吸声。这是一种拒绝让生活沦为生产力或景观的姿态——等待本身成为一种抵抗,一种安静的坚持:仅仅存在,就已然有意义。

Pushing the Stone – Performance Still

EN: This image captures a moment of Sisyphean effort, echoing the myth of endless labor. The act of pushing the stone was part of the installation’s live component, turning the gallery into a stage. The labor is not productive in the utilitarian sense — the stone does not need to move — but it enacts persistence, futility, and resilience as embodied experience.

CN: 这一画面定格了西西弗斯式的努力,呼应无尽劳动的神话。推石头的动作是装置的现场组成部分,把展厅变成舞台。这种劳动并不产生功利性的结果——石头并不需要被移动——但它让坚持、徒劳与韧性成为身体经验。

Tang Xianzu – Coal Portrait

EN:

This work merges portraiture, material research, and identity inquiry. Using coal dust from my hometown in Jiangxi — a region historically rich in both coal and classical Chinese culture — I draw the face of Tang Xianzu, the playwright often called the “Shakespeare of the East.” Here, medium and subject are inseparable: coal is not merely a pigment but a carrier of geological and cultural memory. The choice of Tang Xianzu is also biographical: he and I share the same province, and his plays (The Peony Pavilion, The Purple Hairpin) were my earliest encounters with poetic tragedy. Rather than functioning as a commemorative portrait, the work is part of a performative process — the dust is scattered, fixed, and allowed to leave residue on the paper edges, acknowledging its material instability. Displaying it unframed, with particles loose and vulnerable to air, makes the piece hover between drawing and time-based work. This is simultaneously a homage and an experiment: an attempt to write myself into a longer literary and geological lineage, letting the medium carry both the weight of history and the ephemerality of a breath. CN:

这件作品结合了肖像、材料研究和身份探寻。我使用江西家乡出产的煤炭——一种承载地质与文化记忆的材料——在宣纸上绘制汤显祖的面孔,他被称为“东方的莎士比亚”。 在这里,媒介与题材不可分割:煤炭不仅是颜料,也是历史的载体。选择汤显祖具有自传性意义:他与我同省,他的《牡丹亭》《紫钗记》是我最早接触的诗意悲剧。 作品并非纪念性肖像,而是表演性过程的一部分——煤炭粉末被散落、固定,又在纸面边缘留下不稳定的痕迹,承认它的物质易逝性。作品被无框展示,让粉末暴露在空气里,使其介于绘画与时间性作品之间。 这既是致敬,也是实验:一种把自己写入更长文化和地质谱系的尝试,让媒介同时承载历史的重量与呼吸的轻盈。

Look on My Works!

Growing up in Jiangxi, coal was part of daily survival—fuel for cooking and warmth, a witness to the endurance and decline of my hometown. Later, I turned cigar smoking into a ritual of teenage desire and resistance, inspired by my idealistic reading of Che Guevara. In this work, I use cigar ash as both material and metaphor, letting its fragility mark the paper like two ghostly legs. The title, Look on My Works, quotes Shelley’s Ozymandias—a reminder that all power and monuments turn to dust. This drawing is both a memorial and a question: how do we hold memory when everything drifts away?

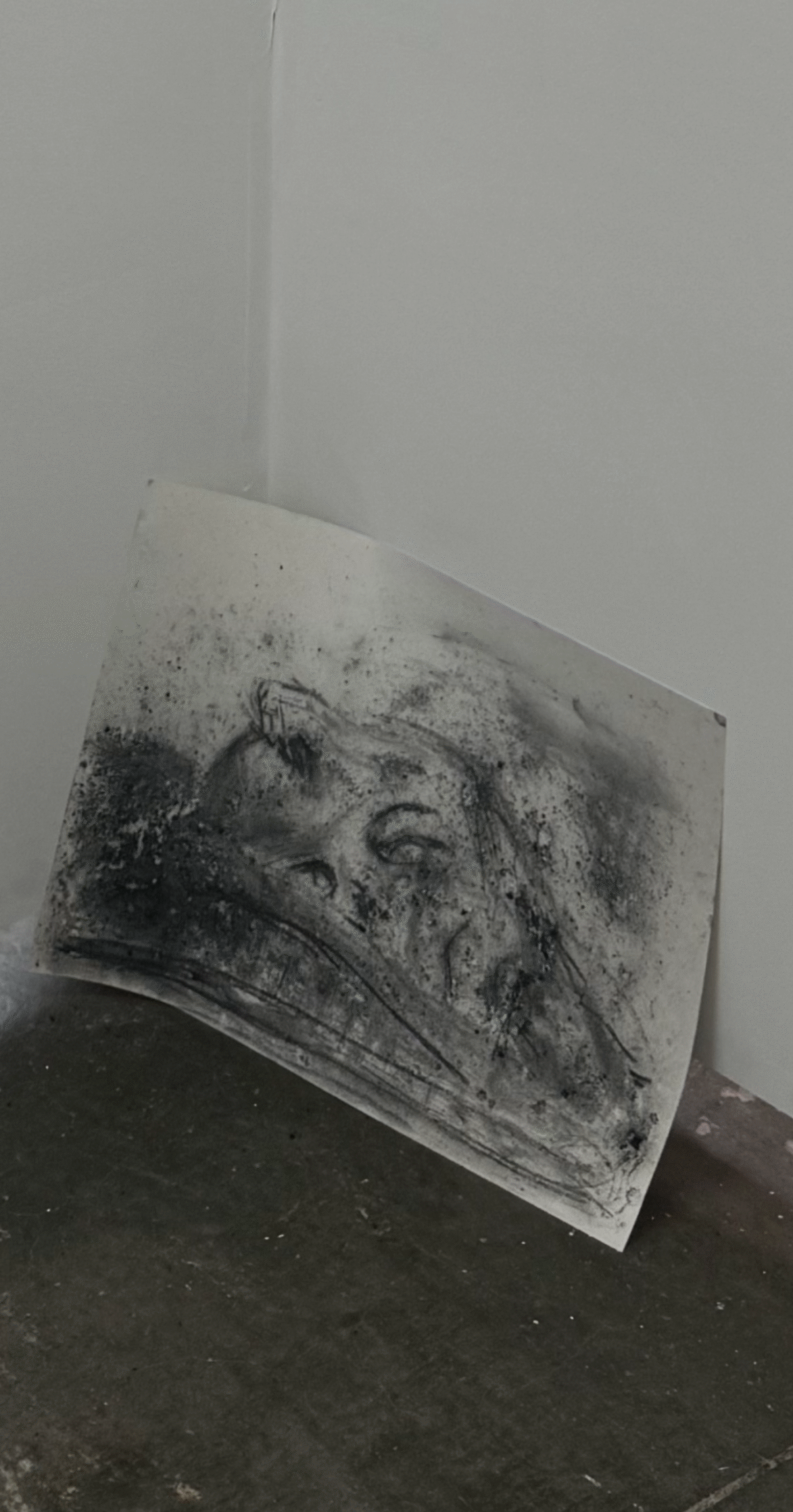

Look on My Works – Ozymandias in the Corner

This work is not simply a drawing but a spatial event. The coal-dust portrait of a shattered head — inspired by Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias — is deliberately placed low to the ground, tucked into a neglected corner of the exhibition space. Its position is crucial: it resists the “white cube” convention of central, monumental display and instead invites an almost accidental, intimate encounter. Inspired by the continuation of Shelley’s poem —

“…Near them, on the sand, / Half sunk, a shattered visage lies…” —

the work humbles itself before time. Its vulnerability is the point: it is not preserved behind glass like a museum artifact but left precarious, exposed to dust and erasure. Medium-wise, it is a hybrid work: drawing as object, site-specific installation, and performance documentation (the act of placing it in the corner is part of the piece). The photograph you see here is not merely a record but an integral layer of the work, emphasizing its ephemerality. Thematically, this piece meditates on ruin and entropy. Shelley’s famous line, “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair,” becomes ironic — not a celebration of power but a quiet acknowledgment that even the mightiest rulers leave behind fragments destined to fade. By allowing the work to sit on the ground, vulnerable and unprotected, I stage a subtle confrontation with the art world’s impulse to monumentalize and preserve. This work is simultaneously drawing, installation, and performance: it is about making fragility visible and turning the exhibition corner into a site of tension, loss, and critical reflection. 标题:《看吧,我的杰作——角落装置》 这件作品不仅仅是一幅绘画,而是发生在空间里的事件。用煤炭绘制的破碎头像——灵感来自雪莱的《奥兹曼迪亚斯》——被刻意放置在展厅的角落,几乎贴近地面。这样的摆放是作品的核心:它拒绝“白盒子”里居中、纪念碑式的展示,转而成为一种边缘化、近乎偶然的发现。 灵感来自雪莱诗句的后半段:

“……不远处,半埋着一张破碎的面孔……”

作品仿佛在时间面前低下头。它的脆弱性正是重点:不被玻璃保护,不被框架固定,而是暴露在灰尘、消逝和抹去的可能之中。 在媒介上,它是复合的:既是绘画,也是场域特定的装置,并且包含行为艺术的成分(把画放在角落的动作本身就是作品的一部分)。这张摄影并不仅仅是记录,而是作品的一层,强调其易逝和悬置状态。 在观念上,它是对废墟与熵增的沉思。雪莱的名句“看吧,强者们,我的杰作,绝望吧!”在这里成为一种讽刺,不再是权力的宣言,而是对帝国和艺术所谓“永恒”的质疑。把作品放在地面,让它暴露、脆弱,构成对艺术界“保存、装裱、纪念碑化”冲动的温柔对抗。 这件作品既是绘画、装置,也是行为,是一次将脆弱展示化的尝试,让展览的角落成为紧张、失落与批判思考的现场。

Dragon Encircling the Mountain – Cigar Ash Drawing

Description:

EN:

This work transforms an intimate, almost rebellious act — smoking a cigar — into a mark-making ritual. The ashes are my drawing material, leaving traces that are at once faint and dramatic. The dragon motif coils around a central mass like a mountain, evoking both Taoist cosmology and adolescent defiance. The piece is best understood as performance residue: the act of smoking, tapping the ash, and dragging it across the page is inseparable from the final image. Photography plays a key role, capturing the drawing at its most alive moment before the ash disperses or smudges. In this work, gesture is foregrounded: the dragon exists only as long as the ash holds its shape. The fragility of the medium mirrors the impossibility of holding on to youth, freedom, or resistance — all are consumed in the same gesture that creates them. CN:

这件作品把一种亲密、带有叛逆性的行为——抽雪茄——转化为书写仪式。雪茄灰成为我的绘画材料,留下既轻盈又戏剧性的痕迹。盘旋的龙环绕着中央的山峰形状,既呼应道家宇宙意象,也唤起青春期对抗与渴望自由的冲动。 作品可以理解为表演的残留:抽烟、弹落烟灰、在纸面拖拽的动作与最终图像不可分割。摄影至关重要,捕捉下灰烬在散落或模糊前最鲜活的瞬间。 这里强调的是动作本身:龙只在灰烬保持形状的时间里存在。媒介的脆弱映照了青春、自由、抵抗无法被保存的事实——它们在创造的同时也被消耗。

scarlett-guan-coal-drawing-bird-study

EN:

This drawing takes inspiration from birds depicted in classical Chinese literati paintings — not merely as naturalistic representations but as carriers of spirit and metaphor. Executed with coal dust, the work connects the gesture of the brush with the raw, smudged unpredictability of coal as a medium. The bird stands still, almost dissolving into the paper, yet it embodies an inner motion — the tension between stillness and the urge to take flight. For me, birds are deeply personal symbols: they speak of my desire for freedom, for transcendence, for stepping outside prescriptive roles. This piece is part of my ongoing “Coal as Memory” body of work, which reclaims coal as more than an industrial residue, using it to trace personal memory, cultural heritage, and emotional impulses. CN:

这幅画取材于中国古代文人画中常见的鸟意象——它们从来不是单纯的自然再现,而是精神与隐喻的载体。作品用煤粉完成,将毛笔的提按顿挫与煤炭原始、不可控的涂抹感结合在一起。 画中的鸟似乎静止不动,又仿佛随时要振翅而去,悬于静与动之间。对我而言,鸟是极为私人的象征:它代表着我对自由的渴望,对超越现实框架的冲动,对摆脱规训的想象。

Bird in Flight – Cigar Ash Drawing

EN:This work is made entirely with cigar ash — a material that carries for me a deep personal charge. I first began smoking cigars in my early twenties, fascinated by the ritual and by the figures who seemed to embody defiance, like Che Guevara. To draw with ash is to transform an act often seen as rebellious or excessive into a mark of creation.

The bird is an avatar of my subconscious: every time I use cigar ash, I find myself tracing forms connected to adolescent impulses — the urge to do something great, to refuse the quiet obedience often expected of women, to claim a freedom that is both bodily and spiritual.

In this photograph, the moment of creation is frozen: ash explodes and falls, the bird takes shape, wings outstretched, caught between appearance and disappearance. The drawing is not just an image but a residue of performance — the gesture, the breath, the risk that the ash could scatter away before fixing — all are part of the work. CN:

这幅作品完全用雪茄烟灰绘制,对我来说,这种材料承载了极强的个人意味。我二十岁出头开始第一次点燃雪茄,被这种仪式感吸引,也被像切·格瓦拉这样象征叛逆的人物打动。用雪茄灰作画,将一种常被视为叛逆或放纵的行为转化为创作的笔迹。

飞鸟是我潜意识的化身:每次用雪茄灰,我画出的形象都和青春期的隐秘冲动有关——渴望成就某种伟大,渴望拒绝女性“乖巧”的规训,渴望身体与精神的彻底自由。

这张照片定格了创作的瞬间:灰烬在空气中炸裂、落下,鸟的形象在出现与消失之间被捕捉。作品不仅是一个画面,更是一次表演的残留——手势、呼吸、灰烬随时可能散去的风险,都成为作品的一部分。

sPalm Glyph — Fate Lines(掌纹字|命纹)

This piece originates from a body-based drawing protocol I developed while researching fate, palmistry, and early writing systems. I first photographed my palm, then traced the major lines—life, heart, and head lines—together with minor branches. From these vectors of pressure and time I composed a single “proto-character,” a mark that does not encode a sound but condenses movement and duration. The form was written with Chinese ink on xuan paper to retain breath, drag, and dry-edge; afterward I digitized and refined the contours into a clean vector so the glyph can migrate across media (print, engraving on stone, silk-screen, or as a sign within installations). Conceptually, the work treats the body as an archive and writing surface: destiny is not a given schema but a diagram you can rewrite. The piece also dialogues with my knotting and coal-based projects—where line becomes knot, seam, fissure, and finally script. Description(CN)

这件作品来自一个以身体为起点的书写方法:在研究命运、掌纹与早期文字系统的过程中,我先为自己的手掌拍照,临摹生命线、感情线、智慧线以及细小的分支纹路,再将这些“压力与时间”的轨迹综合为一个“原始字符”。它不对应具体语音,而是把动作与时间凝缩成一个可读的形体。 我用毛笔在宣纸上书写,以保留呼吸、顿挫与干笔肌理;随后将其数字化、矢量化,使该字符能够在不同媒材中迁移(印刷、石材雕刻、丝网或作为装置中的标识)。概念上,这件作品把身体视为档案与书写面:命运并非固定范式,而是一张可被重写的图。它也与我的“绳结/煤炭”系列互文——线条在不同语境中变为结、缝、裂纹,最终回到文字。

scarlett-guan-leaf-palm-earth-art

EN:

Leaf Palm is a site-specific earth drawing that extends my research on palmistry and destiny into the landscape. I first traced my own palm lines, turned them into a calligraphic figure, and vectorized it as a personal proto-character — a sign of my life path. Here, I translate that glyph into a land-art gesture by arranging fallen leaves on grass, scaling an intimate line from the body to the earth. The work explicitly references Martin Heidegger’s statement: “Poetically man dwells on this earth.” (Heidegger, “…dichterisch wohnet der Mensch…”, 1951). For me, this is not an abstract claim but a practice — dwelling becomes an act of composition. The piece frames everyday life itself as an artistic medium, where even a simple hand sign can become a cartography of presence. Its ephemerality is part of the work: it appears, it may vanish, yet the act of making becomes a way of inhabiting the world. CN:

《叶掌》是一件特定场域的大地绘画,把我关于掌纹与命运的研究延伸到自然之中。我先描摹自己的掌纹,将其转化为毛笔书写,再矢量化成为个人的“原始字形”——象征我的生命轨迹。在这件作品里,我用落叶在草地上描出这一字形,把身体尺度的线条扩展到土地尺度。 作品直接回应海德格尔在《诗意地栖居》(1951)中的名句:“人,诗意地栖居于大地之上。”对我而言,这不是抽象的命题,而是一种行动:栖居成为一种创作。作品让日常生活本身成为媒介,一道手纹也能成为存在的地图。它的短暂性是作品的一部分:它出现、消散,而创作的行为本身就是我在世界中的栖居方式。